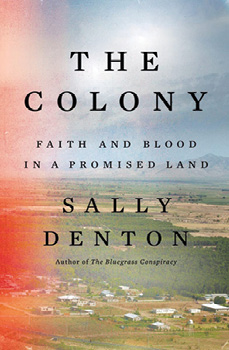

In her ninth book, “The Colony,” the veteran journalist Sally Denton takes readers across the border to a Mormon sect in Mexico.

The New York Times — By Julia Scheeres, June 28, 2022

Women tend to fare poorly in religions created by men. Throughout history, male prophets have claimed divine authority to write laws that perpetuate male power and shunt women aside as intellectual inferiors or evil temptresses who threaten male glory.

Although we reject sexism in other sectors of our society, it is baked into many religious creeds. Nowhere on our continent does a faith based on male supremacy loom larger than in the polygamist sects dotting the American West and northern Mexico, which follow the original teachings of the libidinous founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Joseph Smith. Billing himself as a “prophet, seer and revelator” in 1830, Smith bested the religious start-ups of yore: He claimed that God — viewed as male, always — allowed men to take multiple wives. Smith accumulated up to 40 himself, including a 14-year-old girl — a troubling history that Mormon leaders denied until 2014.

“Central to Smith’s theology was the doctrine that all male devotees were on the road to godhood,” Sally Denton writes in her meticulously researched new book, “The Colony.” She goes on, “In the Mormons’ patriarchal system, a woman could only enter heaven as an appendage to a man, yet a man could take as many women to the eternal kingdom as he pleased.” Unsurprisingly, young men found Smith’s sales pitch very attractive.

Denton, who is an award-winning journalist and the author of eight previous books (including two related to Mormonism), is a descendant of polygamists. In “The Colony,” she traces the lineage of Melissa LeBaron, the plural wife of one of Smith’s early acolytes, to the present-day Colonia LeBaron, a polygamist community of 5,000 people in Chihuahua, Mexico.

“This book is an exploration of LeBaron — the place and the family — in an effort to explain the impulses that drove thousands of women over generations, including ancestors of mine … to join or remain within a novel American religion based on male supremacy and female servitude,” Denton writes.

Bowing to pressure from the federal government, the Latter-day Saints issued a manifesto forbidding plural marriage in 1890. The sudden shift in dogma split the church; fundamentalists, including the LeBarons, fled to Mexico to continue their polygamous lifestyle.

The author couldn’t have found a more bizarro clan to profile than the LeBarons, whose history of murdering family members, mental illness and incest rivals that of the Hapsburgs. One LeBaron patriarch, after 14 years of marriage to one woman, claimed he had a vision telling him that he needed a “quorum” of seven or more wives to attain godhood. Another blamed God for his seduction of underage girls. Yet another incorporated U.F.O.s and extraterrestrials into his teachings. One family member told Denton that a “streak of insanity haunted the family,” the result of generations of marriages between first cousins and even half siblings. Over the years, it has become increasingly difficult for followers to distinguish between their leaders’ “divine” revelations and mental derangement.

Most of Denton’s polygamous sources insisted on anonymity, reflecting a culture ruled by secrecy and fear. Practitioners skirt the law by marrying only the first wife; subsequent wives are relegated to the status of “concubine,” with few legal rights. Whether male practitioners truly believe Smith’s teachings or are only “converted below the belt” — as one woman who fled the colony suggests — is impossible to tease out.

The clan has grown relatively wealthy in Chihuahua, where they own more than 12,000 acres of walnut and pecan orchards that rise from the desiccated landscape like a green mirage. The trees are irrigated with water diverted from communal aquifers and rivers, an action that has provoked ongoing water wars with neighboring farmers.

The LeBarons made headlines in 1972, when Ervil LeBaron ordered a Mafia-style hit on a rival polygamist leader: his own brother. The murder kicked off a 15-year killing spree that claimed 33 lives, as Ervil (known as “the Mormon Manson” in the press) enlisted some of his 13 wives and 54 children to kill his enemies — murders that were financed by drug trafficking, bank robberies and a vast, trans-border car theft ring.

In 2009, the family again entered the news cycle when drug traffickers kidnapped a teenage boy from the colony and demanded a million-dollar ransom. The case caught the attention of Keith Raniere, leader of the Nxivm sex cult, who billed himself as “one of the top three problem solvers in the world” and flew to Mexico to advise the family. Raniere was struck by the “docility and submissiveness” of the LeBaron women, Denton writes, and chose 11 girls, ranging in age from 13 to 17, to bring back to his headquarters in upstate New York, ostensibly to work as Spanish teachers in a school he’d founded, but in reality, according to prosecutors, to groom them as sexual partners. Raniere was unable to solve the polygamists-versus-narcos problem, however, which came to a head in 2019 when gunmen opened fire on a caravan of three cars from LeBaron and a sister polygamist community, killing three women and six children.

I grew progressively angrier as I read this book. While Denton provides an excellent history of a polygamist subculture, she never fully explains why women choose to stay in a religion that treats them so shabbily. But as someone who grew up in a fundamentalist Christian household and understands how self-eroding patriarchal religion can be to girls, I’ll take a stab at an answer. The stranglehold of a dogma embedded in a child’s mind from infancy can be loosened only by exposure to new ideas. But for the LeBaron women — hobbled by chronic pregnancy, economic dependency and lack of a formal education — the odds of escaping that stranglehold are very slim.

“The colony is a magnet for trouble,” one woman who fled long ago told Denton. “They have a good racket. Many of the women are not there by choice.”

Perhaps women should start a belief system based on respect and equality for ourselves and our sisters. Oh wait, we already have one: It’s called feminism. Denton’s book is a testament to what happens when male power, under the guise of religious conviction, goes unchecked.

Julia Scheeres is the author of “Jesus Land” and “A Thousand Lives: The Untold Story of Jonestown.” Her latest book, “Listen, World! How the Intrepid Elsie Robinson Became America’s Most-Read Woman,” will be published in September.

THE COLONY: Faith and Blood in a Promised Land, by Sally Denton | Illustrated | 288 pp. | Liveright | $27.95