A new book investigates the 2019 killings of nine people with ties to the extended LeBaron family, Clémence Michallon reports, and delves into the LeBarons’ complicated history | Monday 25 July 2022 22:22

On 27 June 1988, four murders took place across three different locations. All occurred in Texas at the same time: 4pm. The date, journalist Sally Denton would later note in her book The Colony: Faith and Blood in a Promised Land, marked 144 years since the killing of Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism. The four victims, the youngest of whom was an eight-year-old girl, were all former members of the Church of the Firstborn of the Fulness of Times [sic], a Mormon fundamentalist sect founded by a man called Joel LeBaron. Their deaths had been ordered by Ervil LeBaron, Joel’s brother and the leader of a rival sect, the Church of the First Born of the Lamb of God.

While the four murders were committed in Ervil LeBaron’s name, and under his orders, Ervil had been dead for seven years at the time of the killings. Prior to his death in 1981, the fundamentalist leader had written a manifesto including a list of people to be killed. They were considered infidels, and Ervil had convinced his followers that murdering them was the right thing to do. His influence was such that people kept killing in his name, risking a lifetime in prison, even long after he had passed on.

The murders – which became known as the four o’clock murders in the true-crime space – are part of multiple killings attributed to the LeBaron family over the past 50 years. According to Denton, six LeBaron siblings were indicted in 1992; five were sentenced to time in prison and another was granted immunity in exchange for her testimony. In 1992, the LA Times estimated that “the LeBaron family’s saga spans two decades and involves 25 to 30 murders”, noting that Ervil’s sect “also attracted a handful of non-family followers.” A Daily Beast article published in July this year attributed “as many as 50 members” to “members of LeBaron’s family”, “as well as bank robbery, car theft, drug dealing, and selling guns to drug traffickers.”

Denton’s new book, published on 28 June by Liveright, an imprint of W W Norton & Company, investigates the 2019 killings of nine people (three women and six children) from Mormon enclaves in Mexico with ties to the extended LeBaron family. A contemporary column in The Salt Lake Tribune pointed out they were not members of Ervil’s sect, noting: “While many of the families in the colonies share the surname LeBaron, they are likely of no association to Ervil’s group, most of whom they’ve never met or interacted with.” The killings brought international attention to the family and the apparent tensions between the LeBarons and Mexico’s drug cartels, who were suspected of being behind the attack.

The Colony: Faith and Blood in a Promised Land also serves as a deep chronicle of the LeBaron family’s history, and its place in Mormon doctrine. Released around the same time as two documentaries (Keep Sweet: Pray and Obey on Netflix and Under the Banner of Heaven, the TV series adaptation of Jon Krakauer’s book of the same name), Mormon fundamentalism is currently at the front of the modern true-crime landscape.

The Church of the First Born of the Lamb of God

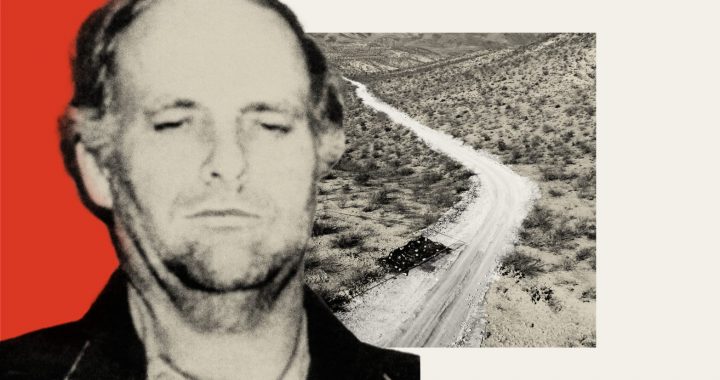

While Ervil LeBaron, having earned the nickname “Mormon Manson” due to the killings perpetrated at his behest, is the most infamous member of his family, the LeBarons’ ties to fundamental Mormonism far predated his adulthood.

In 1924, his father Alma Dayer LeBaron Sr (who went by Dayer) was excommunicated from the mainstream Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for practicing polygamy, which the church renounced in 1890. (Prior to that, polygamy had been a Mormon practice beginning in the 1840s, under Joseph Smith’s leadership.) Ervil LeBaron, the ninth child of Dayer and his wife Maud (one of Dayer’s two wives), was born in 1925. The family settled for a time in Colonia Juárez, a small town in Chihuahua, but, per Denton, were ostracized due to their subscription to polygamy and asked to leave. In 1944, Dayer began establishing Colonia LeBaron, a polygamist community in Galeana, Chihuahua. Dayer died in 1951; four years later, in 1955, his son Joel started the Church of the Firstborn of the Fulness of Times.

Denton says Ervil was initially his brother’s “most passionate devotee”, but their rapport soured. In the late Sixties, Ervil started his own sect, the Church of the First Born of the Lamb of God, and in 1972, Ervil had his brother Joel murdered. The killing marked the beginning of a “ruthless campaign” by Ervil, writes Denton, which would see him order “Mafia-style hits on his many rival polygamist leaders and apostates from his church”.

Blood atonement

As sect leader, Ervil – described by The Daily Beast as “a 6’8” white supremacist and religious fundamentalist who loved to seduce underage girls” – relied on the idea of blood atonement, a disputed concept within Mormon doctrine according to which people who commit certain acts can be redeemed only through the shedding of their blood. (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has rejected the doctrine, as seen here in a statement released in 2010.)

In 1981, The Associated Press noted that Ervil’s “belief that he was ‘the one mighty and strong prophet of God’ and his vow made in 1970 that ‘blood will run to solve our problems’ has led to a reign of terror among Mormon fundamentalists.” At the time, “the number of LeBaron’s former disciples who have died or disappeared over the past two decades” had reached 18. In her book, Denton attributes 33 murders to the killing spree that began with Joel’s death.

From Chihuahua to NXIVM

To talk about Ervil LeBaron is to talk about women and girls – his 13 wives, his daughters, and the 11 girls, “aged 13 to 17”, writes Denton, who traveled from Chihuahua to the US to join NXIVM, Keith Raniere’s cult in upstate New York. Former prosecutor Moira Kim Penza, who led the case against Raniere, told the Times Union in 2019 she believed some of the girls were “exposed to Raniere’s pedophilic and misogynistic teachings” and “groomed to have sex with Raniere”.

“I believe the girls from the LeBaron community were targeted specifically because, having been raised in a polygamist sect, they were more vulnerable to Raniere’s teachings on sexuality, including that it is natural for women to be monogamous and for men to have more than one partner – a philosophy that served Raniere’s own sexual preferences,” Penza told the publication.

Raniere’s cameo in the LeBaron story is at once surprising and predictable: Raniere’s narrative, similar to LeBaron’s, is the tale of a man who used spiritual doctrine in the service of his own desires and interests. (Raniere was sentenced in October 2020 to 120 years in prison after being convicted of racketeering, racketeering conspiracy, sex trafficking, attempted sex trafficking, sex trafficking conspiracy, forced labor conspiracy, and wire fraud conspiracy.)

“Nowhere on our continent does a faith based on male supremacy loom larger than in the polygamist sects dotting the American West and northern Mexico, which follow the original teachings of the libidinous founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Joseph Smith,” wrote author Julia Scheeres in a review of Denton’s book forThe New York Times. To Scheeres (whose own books include the memoir Jesus Landabout her upbringing in a fundamentalist Christian household and A Thousand Lives about Jonestown), “Denton’s book” – and Ervil LeBaron’s story – “is a testament to what happens when male power, under the guise of religious conviction, goes unchecked.”

Ervil LeBaron’s legacy

Ervil LeBaron was arrested, extradited to the US, and convicted in 1980 of having ordered the 1977 murder of Rulon Allred, the leader of another polygamist sect. He was also convicted of plotting to kill his brother Verlan LeBaron, also the head of a different polygamist group, The New York Times reported at the time. Ervil was sentenced to life in prison and was found dead in his cell the following year, in 1981, having apparently died by suicide. Prior to his death, he wrote a long manifesto including a hit list of enemies for his followers to kill.

Denton notes that those killings continued into the Nineties and included the four o’clock murders for which six LeBaron siblings were indicted.

“The families who remained in the Mexican colonies had to contend with threats from Ervil’s followers until the list allegedly went ‘dead’ around 2013,” Mormon consultant, blogger, and podcaster Lindsay Hansen Park wrote in her 2019 Salt Lake Tribune column. Nowadays, she added, “many of the citizens of the Mormon colonies are members of a variety of different Mormon churches – from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to independently practicing Mormon polygamists. Some practice plural marriage and others believe in the principle but don’t practice it, though they all trace their presence in Mexico to it.”

Tensions with drug cartels

The LeBaron name “became common in La Mora” through “intermarriage over the generations”, The Associated Press reported in 2019 citing Cristina Rosetti, a scholar and expert of Mormon fundamentalism. “But since the family name is so widely associated with the church, La Mora residents consider themselves ‘independent Mormons’ to stress they have no connection to the Church of the Firstborn of the Fulness of Times,” the agency noted.

Tensions grew between those communities and the drug cartels in the same area. In 2009, “Mormon families of the same LeBaron name were targeted by drug cartels”, Park wrote. That year, Eric LeBaron was kidnapped by a cartel that demanded a $1m ransom in exchange for his release. (Eric was eventually released; the family has said the ransom was not paid.)

Also in 2009, Benjamin LeBaron, an anti-crime activist, was killed along with his brother-in-law Luis Widmar. The 2019 killings of nine people – Titus Miller, Tiana Miller, Rogan Langford, Krystal Miller, Trevor Langford, Howard Miller, Christina Marie Langford Johnson, Rhonita Miller, and Dawna Langford – were described by relatives as a continuation of the same strand of violence. Earlier this month, a US judge ordered the Juarez cartel to pay $1.5bn to the families as part of a lawsuit.